Listen to the episode:

John Heartfield, the Weimar German artist and overall upstart, once said that the purpose of propaganda was to ultimately make itself obsolete. If you think about it, this actually makes complete sense. If propaganda is really effective then the cause that it’s working towards will eventually, for better or for worse, be won. Therefore, there’s no more need for the propaganda. Its work here is done.

This also makes sense. The best artists are the ones who know how to forge an immediate intimacy with a viewer, to create an authentic moment of connection, and to tell a story that can be easily read and instantaneously received – all of which are pretty crucial components to propaganda. The thing is, though, fine artists never want their art to be obsolete. They want their work to not only be appreciated by their audiences, but also to be remembered. They want to belong to the ages like the old masters they studied. And as we move into Modernism, this becomes especially complicated, this relationship between relating to your audience and belonging to the ages, because the art world was changing dramatically: like I said, fine artists were taking their cues from caricaturists, they were painting one another, they painted the world around them, and they painted quick impressions instead of ponderous, timeless mythological scenes. It’s like they weren’t even thinking about their place in the ages anymore.

Fortunately, the critics were. In his 1863 essay “The Painter of Modern Life,” the French critic Charles Baudelaire looked around his Impressionist Paris and described this complication, this fraught relationship between belonging to your time and to the ages: he wrote that the art that will remain is the art that “distills the eternal from the transitory”; or, put less lyrically: the best art, like the best songwriting, uses the specific here and now to speak to the indefinable stuff of the ages. You can say this about all kinds of art from all kinds of time, really. I mean, call me the daughter of baby boomers if you must, but I’m fairly certain Bob Dylan will be relevant to the struggles of any generation. So Baudelaire saves the day by creating this new standard for defining how art will find its place in history: that the most powerful, resonant art not only speaks to its own audience and to us, it speaks to us because it spoke so authentically to its own audience.

SO THIS BRINGS us back to propaganda. As we’ve already established, really good art speaks to its audience, and really, really good art also speaks to the ages, because really, really good artists draw on both their contemporary society and a deep, institutional knowledge of the Old Masters. So it stands to reason that if fine artists are starting to create propaganda, maybe that propaganda will speak to the ages too.

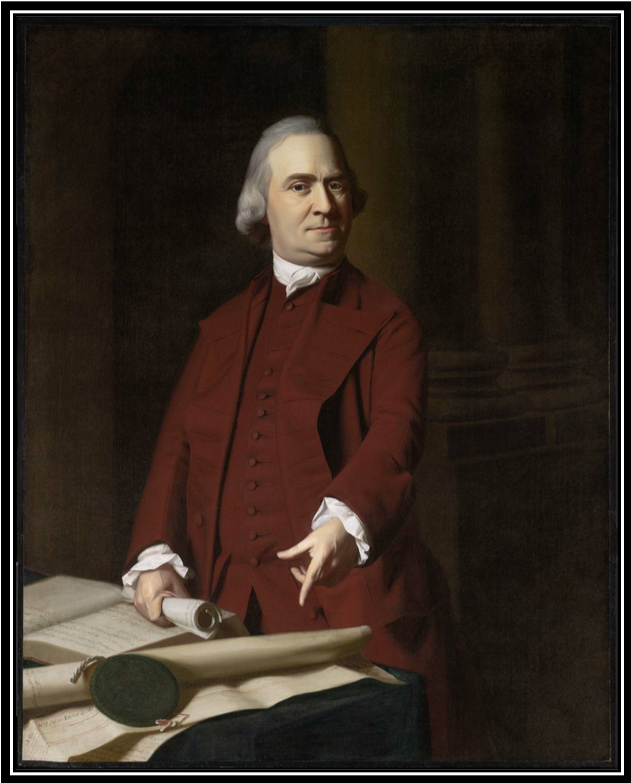

John Singleton Copley was one of these really, really good artists. He is unequivocally one of the best-known fine artists of his period, and his gallery is a jewel in the crown of the MFA’s Art of the Americas wing. His Portrait of Samuel Adams is hung among its fellow Copley portraits in a quiet gallery that smells like sweet, temperature-controlled wood. Its stage is set to be taken seriously as an important artwork from its period: It is surrounded by Paul Revere’s silver and restored federalist furniture.

But make no mistake: this fine painting is a blistering bit of propaganda.

The story this painting is telling is what Copley, and Adams, would have considered Adams’ finest moment: as a representative of the Sons of Liberty, bursting into the office of Governor Thomas Hutchinson—the hated Loyalist Governor of Massachusetts—the day after the Boston Massacre. His right hand is wrapped around a petition signed by the aggrieved citizens of Boston to remove the British soldiers from the colonies; his left hand is pointing sharply at the Charter and Seal, signed by King William and Queen Mary, granting Massachusetts as an independent colony. The painting was completed in 1772, two years after the Massacre, and was commissioned by John Hancock to hang in his living room, where the Sons of Liberty regularly met. It was a shrewd political move on Hancock’s part – he didn’t much like Adams, but respected his revolutionary fervor, and commissioning the portrait by Copley, a highly successful portrait artist and native son of Boston, was an attempt to ingratiate himself into the political scene.

Looking at this painting, it doesn't matter that we’re almost 250 years from the depicted moment. You and I are not disgruntled colonial Bostonians (I mean, not colonial - there’s still the traffic), or revolutionaries, or Governor Thomas Hutchinson, and yet, this is still an electrifying portrait to behold. Copley mutes the background and muddies the overcoat, leaving our eye to beeline directly to the brightly lit point of the story: his head and his hands. His hands are pointing to the law. The expression and the oversized head tells us not only that he means business, but that he knows what he’s talking about, and I’ll come back to that. The commanding body language is such that we would feel subservient to him no matter how high or low this painting was hung. And these little painterly techniques – the high contrast created by the light source, the imposing composition – are just examples of what becomes of propaganda once a great artist gets his hands on it. Copley isn’t just telling the story of this moment to rile the masses, he’s using his knowledge of fine art, and boldly mixing both contemporary and past styles, to rile them effectively.

Copley isn’t just telling the story of this moment to rile the masses, he’s using his knowledge of fine art, and boldly mixing both contemporary and past styles, to rile them effectively.

Take the composition: the light source on the hands and especially the head was a tried and true Neoclassical technique, his period’s technique. Neoclassicism was the movement of democracy. It championed rationalism as the noblest pursuit – there was nothing was more highly respected than getting by on your wits, hence the focus on Adams’ oversized noggin. And there are other clear references to Neoclassicism, which aimed to recapture the republican glory and intellectualism of antiquity, and would have been easily decoded by its audience of heady young revolutionaries in Hancock’s living room. If you squint, or take a step back, the Greco-Roman columns in the background start to emerge, and at once you’re comforted that no matter how passionate or incendiary this figure is, he’s backed up by the calming authority of the law.

But Adams isn’t just illuminated, he’s pushing into our frame. Here is where we see Copley’s dexterity with the techniques of the Old Masters.

With the dark background and active foreground, Copley employs the same technique as Caravaggio did when he painted Christ in the 17th century. And in doing so, he turns us from viewers into participants. We actually become Governor Hutchinson, cowering in front of the formidable Adams. We are as actively engaged as an emotional Baroque audience of Caravaggio, which is quite a feat for an intellectual, political Enlightenment portrait. To mine from such a mishmash of styles, cafeteria painting, if you will, to achieve the most resonant effect, firmly cements Copley as a painter ahead of his time.

But it wasn’t just how Copley was painting, it was how he presents his hero. To present Adams in all his revolutionary glory was, in itself, a revolutionary act. Think about the world Copley was living in: 18th and early 19th century, portrait artists, Copley included, almost exclusively painted their sitters at their most physically idealized, rarely commenting on the action or event taking place. Even wedding portraits barely allude to a wedding. Here, Copley captures Adams not at his most refined, but in his proudest moment, looking fierce and determined, but also, if we’re honest, kind of schlubby. His coat is rumpled, his buttons are misbuttoned, and he’s potbellied and sporting a 5 o’clock shadow. It’s a calculated move on Copley’s part: we’re being told, essentially, that five Bostonians were murdered and there’s hell to pay, and Adams doesn’t have time to button his damn buttons when there’s revolution to be had. This privileging of moment and personality, rather than idealization, is where portraiture is going to go once inherited one hundred years later by Degas and Sargent, two gladiators of modern portraiture.

These small, intimate details, so intentionally rendered, create a portrait of a man whose struggle is universally relatable, in a painting that is universally legible. I’ll say that again: this is a portrait of a man whose struggle is universally relatable, in a painting that is universally legible. You could say that these characteristics are crucial to a painting that has withstood the test of time, but, as it happens, it's also the definition of some really, really good propaganda, whose work, as we’ve just established and with all due respect to Heartfield, is never done.

Next time: please excuse Degas’ dear Aunt Fanny for changing the mid-nineteenth century paradigm of Western art.

Thank you for this great explanation of how to interrogate the portrait of an important person and understand the ways in which the artist takes his audience into the context of the painting.

Helmut Herzfeld became John Heartfield when he came to England and lived here in exile for twelve years, relatively unknown. His German name suggests Jewish heritage; it seems his father was “ historically Jewish “

What might have happened to him had he not left Berlin? (One of his works appears in the history books on the British history curriculum. )